4.全球化与全球环境 Globalization and the Global Environment[112]

本节导读

在全球化背景下,随着世界各国经济的发展和人口的增长,人类活动对自然环境产生的负面影响也越来越大,人类赖以生存和发展的环境受到了空前的污染和破坏,进而使人们的经济福利和生活质量大打折扣;生态环境问题作为非传统安全问题,其严重性和应对的迫切性日益突出。在这“最美好”同时又是“最糟糕”的时代,我们又能为自己、为子孙后代、为地球母亲做点什么?

本篇文章节选自《通向绿色世界之路:全球环境政治经济学》,以全球化对全球自然环境影响为题目,将市场自由主义者(market liberals)、制度主义者(institutionalists)、生物环境主义者(bioenvironmentalists)和社会环境主义者(social greens)等各派观点分别归入“肯定全球化”和“否定全球化”两类,并逐一阐述和对比。作者反复强调,以上各派见解各异甚至大相径庭,归根到底在于其看问题的角度不同,得出的结论也就有所差别。关于全球化与全球环境的关系问题,读者应综合各派观点,不失偏颇、全面客观地看待和认识。

美国前国务卿基辛格早于1975年就指出:“一种崭新的、前所未有的问题已经出现。当今的能源、资源、环境、人口、海洋和空间利用等问题与军事安全、意识形态和领土争端等传统的外交议题处于同等地位。”面对威胁到人类根本生存的环境问题,需要各国以人类共同利益为重,加强合作、协调一致,以“可持续发展”为根本理念去努力谋求问题的解决。美国另一前国务卿鲍威尔于2002年将可持续发展的追求描述为“不是短跑,而是马拉松”。在这场与时间的赛跑中,我们能赢吗?

Globalization and the Global Environment

The interpretation of the effects of globalization on the globe’s natural environment evokes polar[113]reactions.The first,reflective of how market liberals[114]and institutionalists[115]perceive the world,stresses our achievements,our progress over time, and our ability to promote economic well-being as well as reverse and repair environmental problems with ingenuity,technology,cooperation,and adaptation.The second,reflective of how bioenvironmentalists[116]and social greens[117]see the earth, emphasizes environmental disasters and human inequality,problems aggravated and in many cases driven by economic globalization.We now sketch these two broad views of globalization.It should be stressed,though,that while there is a split at the broad level over whether the process of globalization is on the whole positive or negative,each worldview emphasizes different aspects of it.

Global Positive

Market liberals and institutionalists perceive globalization as an engine of wealth creation.Both argue that the globalization of trade,investment,and finance is pushing up global gross domestic product and global per capita incomes,which they see as essential to finance sustainable development.Over the period 1970-2000,one of heightened global economic integration,worldGDP(inconstant1995U. S.dollars)nearly tripled from US$13.4 trillion to US$34.1 trillion.The annual per capita global growth rate from 1980 to 1990 was 1.4 percent;from 1990 to 1998 it was 1.1 percent.

Market liberals and institutionalists both see globalization as an overall positive force for the environment because it generates the wealth necessary to pay for environmental improvements.Market liberals argue that such improvements will follow naturally from the functioning of open and free markets.States and institutions certainly have an important role to perform in terms of making and enforcing environmental policy,but it should be a minimal and market-friendly one.Globalization, by stressing liberalization of trade,investment,and finance,is also lowering inefficient trade barriers and state subsidies.This means fewer market distortions—such as prices that undervalue a natural resource.It means,too,fewer barriers to corporate investment in developing countries.

Institutionalists see a somewhat greater role for the state,and also see a need to build global-level institutions and agreements to more actively guide economic globalization(which to some extent arise naturally from the process itself).The goal is to help states,for example,advance to a higher order of development with as little environmental damage as possible.The UNEP Global Environment Outlook nicely summarizes the institutionalist case:

The pursuit of individual wealth on a global economic playing field made level by universal governance mechanisms to reduce market barriers can…open the way to a new age of affluence for all.If developing country institutions can be adapted to benefit from the new technologies and the emerging borderless economy,and if appropriate forms of global governance can be created,the rising tide of prosperity will lift everyone to new heights of well-being.

Market liberals and institutionalists stress,too,the need to evaluate the environmental effects of globalization within a historical perspective.For them it is particularly important to plot and analyze global trends.Political scientist Bjorn Lomborg[118], an outspoken and controversial academic who is perhaps the strongest advocate of understandi ng the global environment in terms of global statistics,writes:“Mankind’s lot has actually improved in terms of practically every measurable indicator.”He warns against relying on“stories”(examples),because this can distort the analysis of progress,creating either an overly optimistic or pessimistic assessment.Lomborg continues:“Global figures summarize all the good stories as well as all the ugly ones,allowing us to evaluate how serious the over-all situation is.”He further admonishes those who accept data uncritically,citing examples where scholars have come to accept a“sweeping statement”as fact when the so-called fact has no statistical base,instead resulting from“a string of articles,each slightly inaccurately referring to its predecessor”(with a far more modest original source).Lomborg argues,too,that some groups,like Greenpeace[119]and the Worldwatch Institute[120], have a vested interest[121]in painting a picture of a world in crisis.It is their job;it justifies their moral and financial existence.

Look,say market liberals and institutionalists,at the world at the beginning of the twentieth century.Back then life was short and full of hardship and suffering. About a third of the global population faced possible starvation.Infectious diseases like typhoid,tuberculosis,botulism[122],and scarlet fever(often spread in contaminated food,milk,and water)were a leading cause of death.Global life expectancy[123]was a mere 30 years.Even in the United States it was just 47 years,with infant mortality at a rate of 1 in 10.Great progress has been made since then,not coincidentally,market liberals in particular say,as the world has become more globalized.Food production has surpassed population growth,and today less than onefifth of the world’s population is malnourished[124],compared to 37 percent in 1969-1970.Even in the Third World the average person now consumes 38 percent more calories than in 1961.It is now widely argued that famines that occur today are a result of government mismanagement,not a shortage of food.

Vaccines,antibiotics[125],and better medical care now save millions of lives.So do refrigeration,pasteurization[126],and safer food-handling practices.As a result global life expectancy is far higher today—now over 66 years.Steady rises in life expectancy have occurred in both low-and high-income countries,and there is every reason to expect these trends will continue.Economist Julian Simon sums up the case:“The standard of living has risen along with the size of the world’s population since the beginning of recorded time.There is no convincing economic reason why these trends toward a better life should not continue indefinitely.”Market liberals believe that the process of economic globalization itself will spread higher standards of living around the world because of its ability to generate economic growth.Institutionalists see the potential for globalization to raise living standards via economic growth,but argue that global institutions that promote cooperation on these fronts have been and still are necessary to ensure that this happens.

Progress on the food and health fronts has been accompanied by a much larger global population,and some see a direct causal[127]link here.From 1 billion in 1804,world population had doubled by 1927(123 years later),and jumped to 3 billion by 1960(33 years later).By 1999 it had doubled again to 6 billion(just 39 years later).

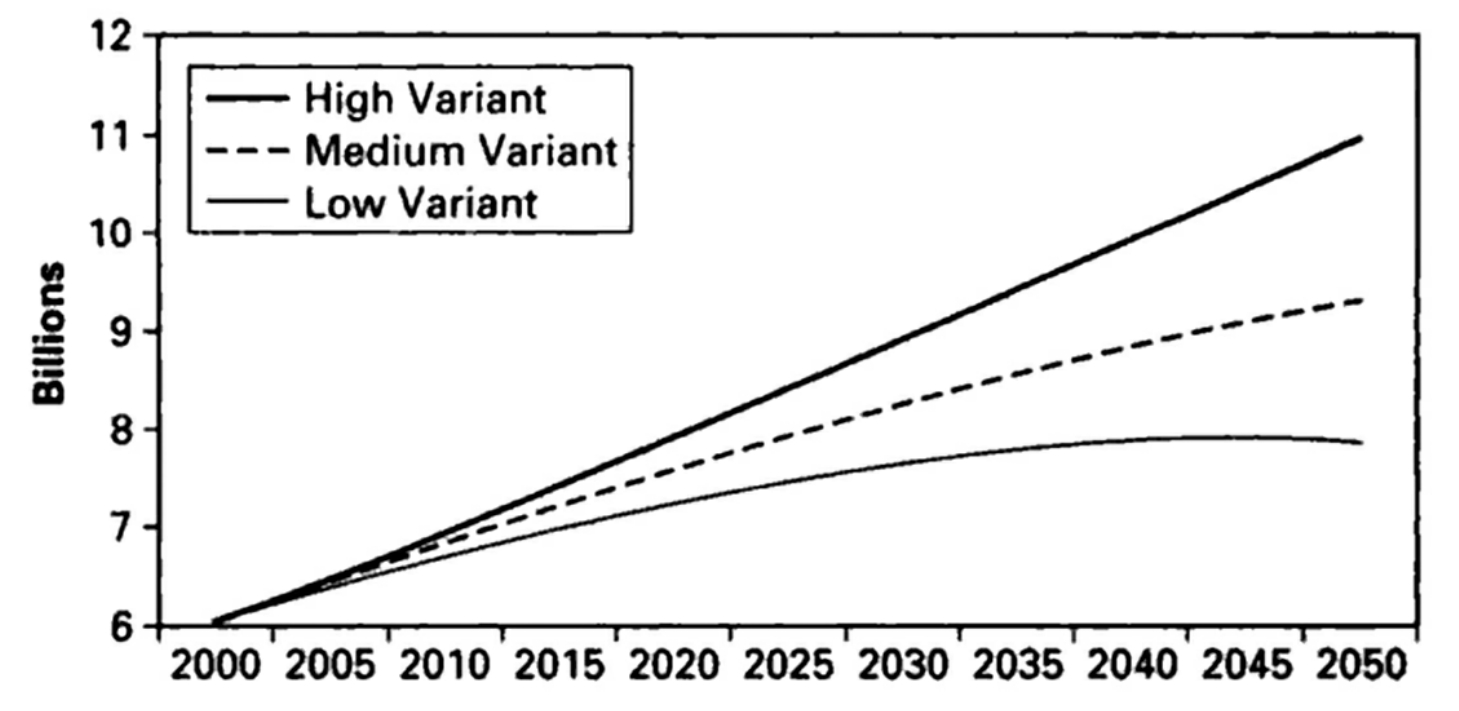

The global population is now well over 6 billion and is making steady progress toward 7 billion.Most analysts expect it will continue to rise into the foreseeable future,leveling off at 8-11 billion by 2050.Figure 2.3 provides three population projections for 2050:a low of 7.9 billion,a middle of 9.3 billion,and a high of 10.9 billion.(The difference is based on alternative possibilities of future birth and mortality rates.)The most likely scenario is the middle one.But for market liberals, even the highest estimate shows that the global community has managed to overcome the threat of exponential[128]population growth.

Figure 2.3

World population prospects.Data source:Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the UN Secretariat,2001.

An earth with 6 billion people,market liberals point out,is not anywhere close to reaching the limits of its capacity.Abundant resources remain.And waste sinks[129]are far from full.Market liberals assume humankind will be able to provide a decent standard of living for all well into the future,provided a free and open global economy is encouraged.Higher incomes and more modern economies allow for higher levels of education for the general population and empower women with more choices.This naturally lowers birth rates.The history of the world’s most advanced economies in Europe,North America,and Asia since the Industrial Revolution some 300 years ago demonstrates this conclusively.Institutionalists are more cautious,recognizing that there may be some scarcities associated with population growth,but they argue that global cooperation on improved education,economic development,and family planning can help address the problem.

For both institutionalists and market liberals,the global community has demonstrated it can solve global environmental problems.Biotechnology has,for example, produced crops able to resist insects and diseases as well as grow in dry and inhospitable areas,and both groups see this as having great potential for improving global food supplies.Market liberals argue that these technologies will spread via market mechanisms and benefit farmers in rich and poor countries alike.Institutionalists have a bit less faith in the global marketplace to spread these benefits equally.While they see the potential of such crops to address future food needs, they argue for public funding for intergovernmental research that focuses on developing bioengineered crops that will benefit the poorest countries.

Perhaps the most successful global cooperative effort was the one to reduce the amount of chlorofluorocarbons[130](CFCs)released into the atmosphere.CFCs were invented in 1928.Production and consumption rose quickly from the 1950s to the 1970s,mainly for use in aerosols,refrigerators,insulation,and solvents.In 1974 scientists discovered that CFCs were drifting into the atmosphere and depleting the ozone layer.This layer protects us from the harmful effects of ultraviolet sun rays, which can contribute to skin cancer and cataracts[131],decrease our immunity to diseases,and make plants less productive.In the decade after 1974 global negotiators worked on a collective response to this problem.This effort gained momentum in 1985 aftera“hole”(reallyathinning)intheozonelayerwas discovered over the Antarctic.In that year the global community concluded the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer.The 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer was adopted within two years and set mandatory targets to reduce the production of CFCs.The Montreal Protocol entered into force in 1989. Amendments to strengthen the Montreal Protocol were made in London in 1990, Copenhagen in 1992,Montreal in 1997,and Beijing in 1999.The result was a significant lowering of CFC production.

The UN Environment Programme(UNEP)predicts that the ozone layer will repair itself and return to pre-1980 levels by 2050.Institutionalists in particular see this as a resounding example of global cooperation to solve an environmental problem. There has been wide acceptance of the global agreements and strong compliance with them.Market liberals also like this example because it demonstrates the ability of markets to respond to a global environmental problem with the development of substitutes that are less harmful.

Global Negative

Unlike market liberals and institutionalists,bioenvironmentalists and social greens see economic globalization as the cause of many of the world’s environmental and social ills,rather than as its potential savior.Both bioenvironmentalists and social greens agree with market liberals and institutionalists that it is driving global macroeconomic growth—but this growth is driving the overconsumption of natural resources and the filling of waste sinks.Moreover,economic growth is not enough to ensure well-being in a society.For bioenvironmentalists economic growth also partly explains the exponential growth of the global population,which for them is of primary concern.But social greens reject the bioenvironmentalists’population argument and focus instead on the way globalization,in their view,contributes to global economic inequalities that exacerbate[132]environmental problems.

Bioenvironmentalists and social greens are far more critical of the so-called progress of our so-called creations and advancements in the era of globalization. The former president of the Nature Conservancy[133]put this well:“In the end,our society will be defined not only by what we create,but by what we refuse to destroy.”Humans certainly live longer.And higher incomes and better medicine and sanitation have undoubtedly made the lives of some more comfortable.Yet such data can also hide disturbing trends.Especially worrying is the steady rise in global cancer rates, even when adjusting rates for an aging population.Every year 6 million people die of cancer.Ten million more are diagnosed with cancer.Only cardiovascular disease[134]kills more people in industrialized countries.Scholars like philosopher Peter Wenz believe that the probable causes of higher cancer rates arise from the artificial changes to our living environments.There seems to be little cancer in traditional societies.One of the most significant causes of cancer in industrial societies for these scholars is the increasing volume of pesticides[135]in the global ecosystem. In the United States alone farmers now use over a billion pounds of pesticides per year,compared with 600 million per year in the 1970s and 50 million per year in the 1940s.Cancer specialists,Wenz notes,concentrate on finding the“cure”rather than the“cause”of cancer,partly because uncovering the causes would challenge“our entire way of life.”

While market liberals and institutionalists tend to focus on the social and political history of the last few hundred years,bioenvironmentalists in particular like to look at the impact of globalization against the background of geological time.The universe is about 15 billion years old.Earth is about 4.6 billion years old.Modern humans have existed for just over 100,000 years and civilization for about 10,000 years.Within this time frame it is clear that humans have become a threat to the planet in a remarkably short period of geological time.Philosopher Louis Pojman provides a vivid image of this:

If we compacted the history of the Earth into a movie lasting one year,running 146 years per second,life would not appear until March,multicellular organisms not until November,dinosaurs not until December 13(lasti ng until December 26), mammals not until December 15,Homo sapiens[136](our species)not until 11 minutes before midnight of December 31,and civilization not until one minute before the movie ended.Yet in a very short time,say less than 200 years,a mere 0.000002% of Earth’s life,humans have become capable of seriously altering the entire biosphere.In some respects we have alteady altered it more profoundly than it has changed in the past billion years.

With this outlook on time,bioenvironmentalists argue that we will soon reach the limits of the earth’s biological capacity to support human life.

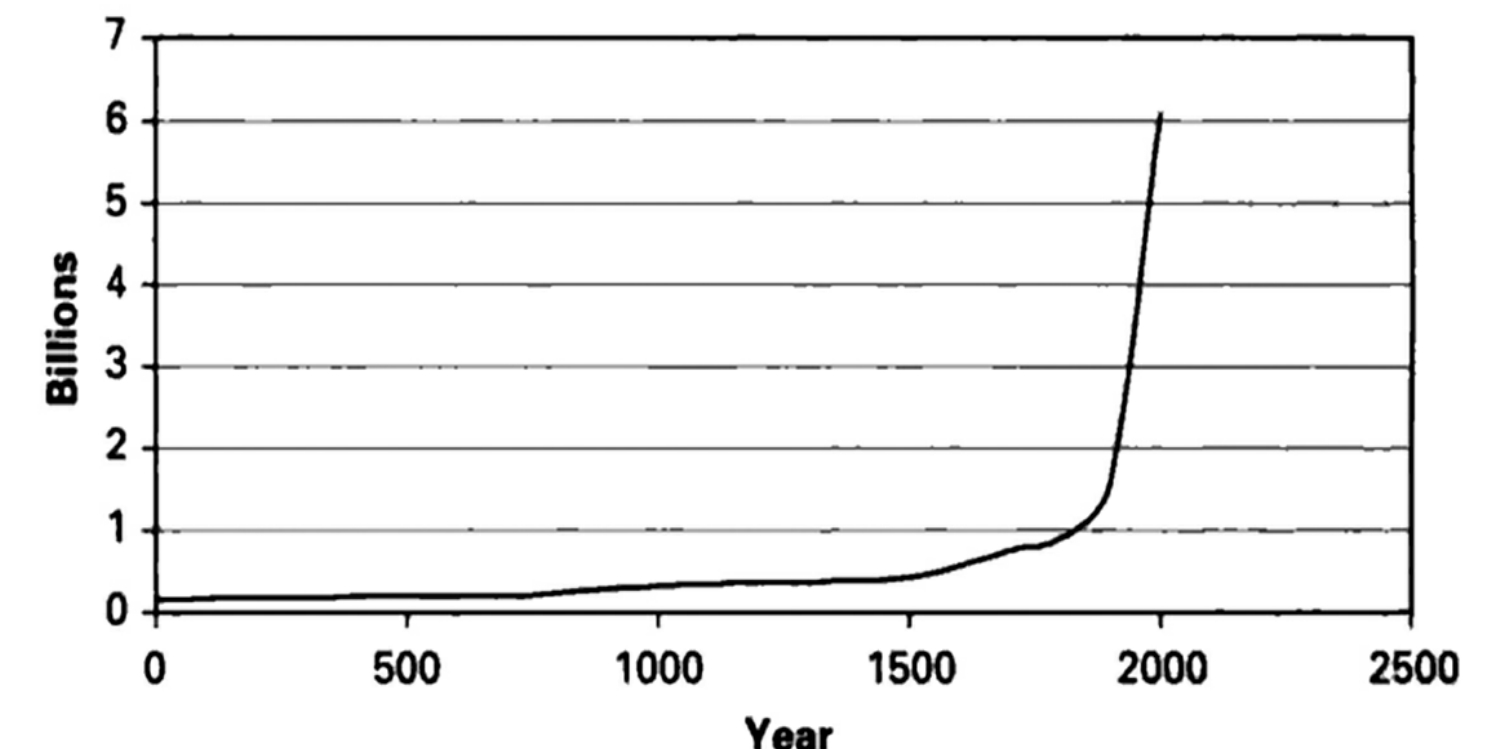

For bioenvironmentalists,human population growth is often the most central part of the problem—for them linked to both economic growth and globalization.They argue that a much better reflection of population patterns arises when we begin in AD 1(see figure 2.5).Each year the global population increases by approximately another 80 million.Since 1950,an era of rapid globalization,the world’s population has grown more than it had in all of human history.Even accepting the midrange estimate of population growth in figure 2.3,by the middle of this century it will exceed 9 billion—another 3 billion people to feed,clothe,and house.Over 85 percent of these people will live in the poor countries.Half of the population growth will occur in just six countries:India(with 21 percent of the total increase), China,Pakistan,Nigeria,Bangladesh,and Indonesia.Over this time the populations of the forty-eight least developed countries will triple[137]in size,already areas of terrible poverty and hardship.

Figure 2.5

World population:AD 1-2000.Data source:Facing the Future:People and Planet: www.facingthefuture.org.

Bioenvironmentalists stress that the current rate of population growth means the planet is increasingly awash[138]with consumers,each demanding a portion of the earth’s resources.One noteworthy indicator of rising consumption in an age of globalization is the steady increase in the number of motor vehicles.Every year the world has absorbed another 16 million new vehicles on the road.Passenger cars now account for 15 percent of total global energy use.Environmental trends confirm the disastrous consequences of such consumption.The air in the rich industrialized countries has undoubtedly become less polluted since the 1960s,but it is now much worse in the developing world—especially in megacities like Tehran,New Delhi,Cairo,Manila,Jakarta,and Beijing.The planet has absorbed 100,000 new chemicals since 1900.Over the twentieth century total carbon dioxide emissions grew twelve times.In the Third World more than 90 percent of sewage and 70 percent of industrial waste is still disposed of(untreated)into surface water.

Global water consumption rose six times from 1900 to 1995.Dams,canals,and diversions[139]now disrupt almost 60 percent of the world’s largest rivers.Deserts now threaten one-third of the world’s land surface and the World Health Organization estimates that 1.1 billion people do not have access to clean water.Diseases from bad water—like dysentery[140]and cholera[141]—kill 3 million people each year.During the last century the world lost half of its wetlands.Around 30 percent of the world’s coral reefs are gone and 18 percent are now at risk.Nearly 70 percent of commercial global marine fish stocks are now overfished or are at the biological limit.One-fifth of the world’s freshwater fish species are extinct or endangered.Every day 68 million metric tons of topsoil washes away.Every day 30-140 species go extinct.The Worldwatch Institute,in the State of the World 2003,points to the dire state of global biodiversity,noting that“prominent scientists consider the world to be in the midst of the biggest wave of animal extinctions since the dinosaurs disappeared 65 million years ago.”The future of global biodiversity under current trends looks bleak[142]. A study by nineteen scientists published in the journal Nature in 2004 predicts that a temperature rise from global warming of 0.8°-2.0°C will“commit”18-35percent of animal and plantspecies“to extinction”by the middle of the twenty-first century.Other factors attributed to global warming—such as higher concentrations of carbon dioxide—could mean an even higher rate of extinctions.

The history of deforestation is typical of the destructive impact of the global political economy.Almost half of world’s forests are now gone.Between 1980 and 1995 alone,over 180 million hectares of forest were lost,mostly in developing countries.That is six times the size of the Philippines,ten times Cambodia,and sixty-four times the Solomon Islands.Frontier forests(defined by the World Resources Institute[143]as large and pristine enough to still retain full biodiversity)are under some of the greatest pressures.Asia,for example,has lost almost 95 percent.The Philippines no longer has frontier forests.Vietnam,Laos,Thailand,and Burma will soon follow.Cambodia has just 10 percent,Malaysia just 15 percent,Indonesia only 25 percent,and Papua New Guinea only 40 percent.

Social greens,too,point to the steady decline in the state of the global environment in an age of globalization.They agree strongly with bioenvironmentalists that economic growth and overconsumption are serious threats to the planet.Yet unlike bioenvironmentalists,they do not focus on population growth as a primary driver of such problems.They point out that growth in consumption of forest products,food, and water,for example,far exceeded population growth over the past thirty years. Instead,they place their main focus on global inequality and its associated environmental problems—those linked to both overconsumption among the wealthy and the dispossession[144]of the poor from their traditional lands.

For social greens,economic globalization is the primary cause of this inequality. It is seen as reinforcing neocolonial relationships between rich and poor countries, as well as changing production patterns in complex ways that have serious environmental implications.The International Forum on Globalization[145],an international group of activists and academics opposed to globalization,points out that today’s world is“in a crisis of such magnitude that it threatens the fabric of civilization and the survival of the species—a world of rapidly growing inequality,erosion of relationships of trust and caring,and failing planetary life support systems.”Life may be easier—and perhaps even better—in sections of the wealthier countries(although not in the slums).But in much of the developing world it is worse.Since 1972 the number of people living in extreme poverty(less than US$1 a day)has grown to 1.2 billion people.Almost half the world’s population(2.8 billion)survives on less than US$2 per day.

There is not enough food in many countries.In fact,even though global food production is now higher,in many parts of the world,such as in Africa,food production has lagged behind population growth over the last two decades.In India, where one-third of the 1 billion people live in poverty,over half of the children are undernourished[146].Worldwide,over 840 million people suffer from chronic malnutrition,which contributes to 60 percent of all childhood deaths.And nearly 11 million children die unnecessarily every year(that is,from preventable and treatable causes).Of these,8 million are babies,half of whom die in the first month of life.At the same time,obesity[147]rates are rising fast in the world’s wealthy countries—in the United States,for example,it went from 12 percent of the population in 1991 to 17.9 percent in 1998.The largest rises in obesity are among 18-to 29-year-olds. In 1999 over 60 percent of all adults in the United States were overweight.Obesity and physical inactivity now account for over 300,000 premature deaths annually in the United States alone.In late 2001 the U.S.Surgeon General issued a“call to action”to address the crisis of obesity,claiming“overweight and obesity may soon cause as much preventable disease and death as cigarette smoking.”

Great inequality is also seen in the distribution of disease.Infectious diseases remain the number one cause of death worldwide,accounting for roughly a quarter of total global deaths.Over 13 million people die each year from diseases like AIDS,malaria[148],tuberculosis,cholera,measles[149],and respiratory diseases[150],most of these in the developing world.These high rates of death from such diseases only contribute to further poverty.In some African countries,life expectancy has fallen,mostly because of AIDS,malaria,and war.The AIDS pandemic started two decades ago.Now over 60 million people are infected with HIV,with numbers rising rapidly especially among the young(half of all new HIV infections are adolescents).In 2001 AIDS killed 3 million.The UN predicts that 68 million more will die prematurely of AIDS by 2020.Of these,55 million will live in sub-Saharan Africa.Already AIDS has lowered the average life expectancy in this region from 62 to 47 years.In Botswana,Namibia,and Zimbabwe,life expectancy has dropped from 60-70 to 38-43 years.In Tanzania,40 percent of the population is now dying before the age of 40.Across Africa,there are about 5,500 funerals a day for AIDS victims.UN AIDS has predicted that one in every five adults in Africa will die of AIDS in the next ten years,destroying the social fabric of much of Africa.The death rates from AIDS are much higher in the developing world because of that region’s lack of access to the latest drugs and treatments that are currently available in the rich industrialized countries.

Social greens argue that this represents unnecessary suffering on the part of the majority of the planet’s inhabitants.The inequality that has accompanied economic globalization is the driver not just of poor social conditions for many,but also of environmental problems.The poor are put in situations where they are uprooted from their lands and forced to degrade what lands they can just to make ends meet. And the rich,meanwhile,overconsume and contribute to a worsening of industrial pollution.For these thinkers,it is not surprising that pollution levels may be falling in rich countries,because globalization has enabled the types of production that pollute most to migrate to developing countries,in the form of foreign direct investment.The rising levels of pollution in the rapidly industrializing developing countries of Southeast Asia and Latin America are evidence of this,according to social greens.This transfer of environmental degradation[151]from rich to poor countries has direct and negative impacts on the lives of the world’s poorest people.

The technological solutions offered up by Western science are not a potential savior for bioenvironmentalists and social greens.The technological transfers of globalization are in fact often a deceptive solution,the heroin of market liberals and institutionalists,temporarily allowing societies to deflect[152]a problem into the future or into another ecosystem.They also have much less faith than institutionalists in the ability of global institutions to guide globalization to ensure that it does not cause further environmental problems.Social greens in particular worry that global organizations and agreements can become props[153]of capitalism,as is the case with the World Bank,International Monetary Fund(IMF),and World Trade Organization(WTO).

Agricultural biotechnology is just one example where social greens and bioenvironmentalists are skeptical of Western technology and institutions.Critics of genetically altered[154]crops argue that they pose enormous ecological and health risks—from genetic pollution and erosion,to potential allergic reactions.These crops are also seen as reinforcing inequalities and as giving power to the transnational corporations that patent them.Global institutions,including the World Bank and the WTO,have continued to promote these technologies as beneficial,despite growing concern over their use.Many social greens,however,still see a need for global institutions,just not the ones we currently have.The International Forum on Globalization summarizes this position succinctly:

There is certainly a need for international institutions to facilitate cooperative exchange and the working through of inevitable competing national interests toward solutions to global problems.These institutions must,however,be transparent and democratic and support the rights of people,communities and nations to self-determination.The World Bank,the IMF,and the World Trade Organization violate each of these conditions to such an extent that[we]recommend that they be decommissioned and new institutions built under the authority of a strengthened and reformed United Nations.

Bioenvironmentalists and social greens also have less confidence in the value of international regimes to slow or resolve global environmental problems than other thinkers do.Certainly most would agree that the global effort to reduce the production of CFCs was successful.But this was an exceptional case,one that tells us little about our ability to handle future global environmental crises.The causes and consequences of the depletion of the ozone layer were relatively straightforward. Skin cancer,one of the most visible consequences of less ozone,was a particular worry.In the mid-1980s CFCs were produced by only twenty-one firms in sixteen countries,and developed countries were responsible for about 88 percent of production.Especially important,by 1988 the chemical company DuPont[155],which accounted for one-quarter of global CFC production,had found an affordable substitute to CFCs.The economic cost of phasing out[156]CFCs was therefore minimal.

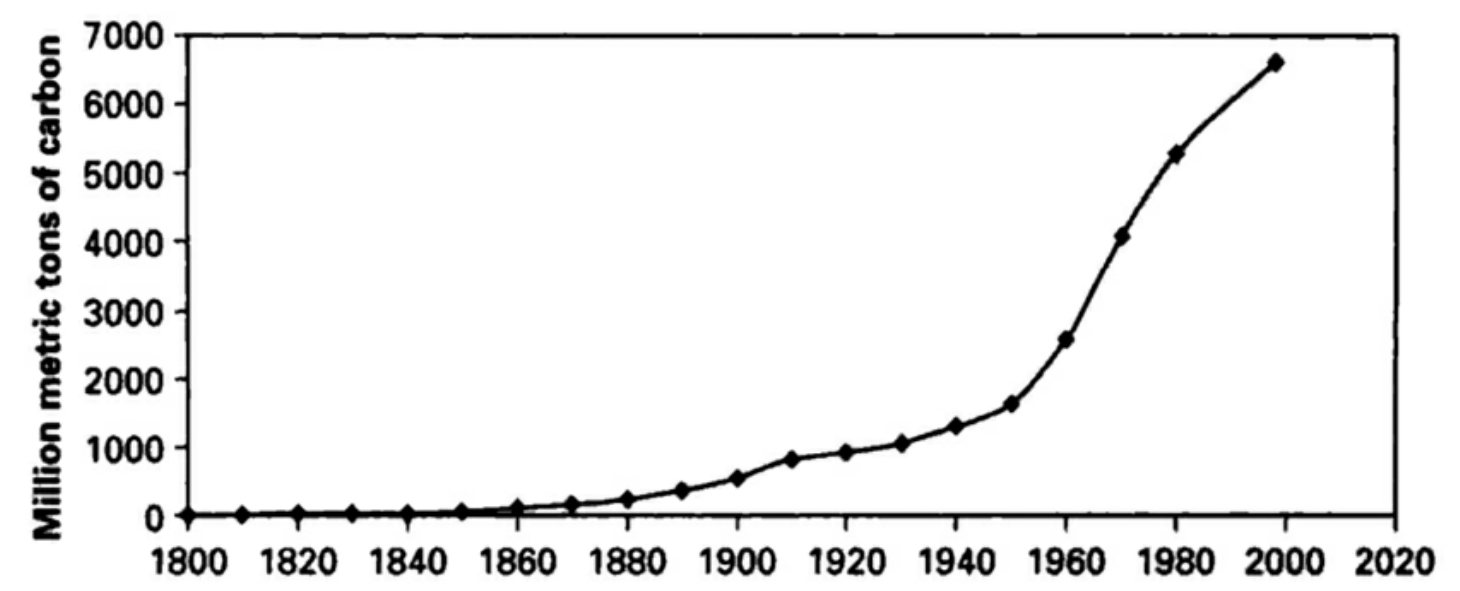

Most global environmental problems,say bioenvironmentalists and social greens, involve far greater complexities and uncertainties than the ozone case and will require far greater sacrifices to solve.Take global warming.The UNEP reports that the mean global surface temperature has risen by 0.3°-0.6°C in the last 100 years. This may not seem like much.But it was the largest increase of any century over the last millennium.The problem appears to be getting worse,because the 1990s was the warmest decade and 1998 the warmest year.For bioenvironmentalists, trends like the one in figure 2.6 indicate our failure to act.

Figure 2.6

Global CO2emissions from fossil-fuel burning,cement manufacture,and gas flare. Data source:Marland,Boden,and Andres 2001.

Global warming especially alarms bioenvironmentalists and social greens,because the three main greenhouse gases(carbon dioxide,methane[157],and nitrous oxide[158])arise from core economic activities(automobile use,electricity generation, factories,agriculture,and deforestation),while the main consequences(rising seas, severe storms,drought,and desertification[159])are beyond the lifetimes of politicians and business leaders—perhaps occurring in 50 to 100 years.And the impacts, when they are most severe,will be mostly felt by the poor,marginalized[160]peoples of the world.Obviously,lowering greenhouse gas emissions will involve major changes to global economic production and consumption patterns.It will require,too,governmental,corporate,and personal sacrifices.Substituting CFCs,say these thinkers, is just not a comparable sacrifice and it is overly naive to believe that it demonstrates that the global community has the collective capacity to act quickly,coherently,and effectively whenever a problem is deemed urgent enough.Any progress on climate change agreements,rather,is more likely linked in some way to corporate strategies to break into renewable energy[161]markets.

Conclusion

This chapter has shown the power of globalization as a force of economic and,at a slower rate,societal and political change.Each worldview brings its own lens to the process,illuminating different aspects—some more positive,others more negative. Each view thus brings different insights into the implications of globalization for the environment.

The market-liberal lens focuses on the benefits of growth and the power of free markets to foster it.For market liberals globalization is a force of good,an engine of progress.It promotes efficient production and trade of goods,diffusing appropriate technologies to areas with natural labor and resource advantages.It promotes investment that brings in environmental technologies,critical funds,and better management.This advances the economies toward less destructive activities by diversifying the sources of economic growth,which in the long run allows economies to shift away from a heavy reliance on natural resource exports.Globalization also means more macroeconomic growth,raising per capita incomes throughout the world.The higher national per capita incomes that arise from embracing globalization are creating the societal and political will to tackle national,and ultimately, global environmental problems.In the long run economic growth extends lives,improves health care,and raises national environmental standards.Globalization allows for even more wealth.Such wealth will allow for even more economies to shift away from agricultural and industrial production and toward knowledge-based economies.

The institutionalist lens is sympathetic to the points raised by market liberals, but focuses more specifically on the international cooperation necessary to bring those benefits to fruition.Institutionalists agree that economic growth and free markets can have enormous benefits for the environment.Yet they argue that globalization should not be seen as a panacea[162].The process,like any dynamic force,is producing both positive and negative changes for the global environment.It is good in macro-economic terms.It is raising global wealth;it is fostering innovation.But the rewards are not always equitable[163].At times,globalization seems to aggravate pockets of environmental degradation and inequality.From an institutionalist perspective,it is therefore best to guide globalization—to use institutions and cooperation and intelligence to maximize the economic benefits and minimize the social inequities.This requires strong national and local governments as well as powerful global organizations.The communication technologies of globalization are advancing this cause,by integrating cultures,fostering awareness,and creating global norms, standards,and sympathies that encourage cooperative efforts to address national problems like malaria or global problems like climate change.The globalization of norms,codes of conduct,environmental markets,environmental organizations,and international law is deepening global environmental governance,adding another layer of control above national-government regulations.

Bioenvironmentalists look at globalization through a very different lens.Instead of seeing opportunity in globalization,they focus on the scarcity it exacerbates.For these thinkers the future is bleak.Globalization props up unsustainable population growth in developing countries,as the rich drop food and medical supplies into poor countries with population growth rates embedded in a culture of poverty. Globalization is also herding populations into overcrowded cities or fragile ecosystems(like onto land cleared of its rainforests),and turning rural areas into vast and specialized farms to feed the cities,often in distant lands.At the same time,the globalization of trade,investment,and financing is accelerating global economic growth.This creates more output and more consumption.It creates,too,more opportunities for the rich to over-consume and waste resources,deflecting the ecological impacts of this consumption overseas or into the global commons[164].Globalization here is little more than“eco-apartheid.”It is deepening the global culture of consumption for consumption’s sake.People are losing the sense of“enough,”as the rising rates of obesity in the developed world show.Ingenuity and technology can certainly help to mitigate particular problems.Yet technology cannot solve the ecological consequences of globalization.Solutions can only begin to occur once the human species accepts that it is now beyond its carrying capacity.

Social greens agree with much of the bioenvironmentalist analysis of the ecological consequences of globalization.Yet their lens focuses much more on the social injustice arising from globalization than on scarcity per se[165].Social greens see globalization as the driving force behind the spread of global inequality and large-scale capitalism and industrial life,which for them are core causes and consequences of the global ecological crisis.Inequality and the imposition of industrialism contribute to the eradication of the rights of indigenous peoples,women,and the poor, and to the destruction of culture as capitalists reconstruct societies into new markets and production nodes[166].These forces are eroding the autonomy of communities and creating a consumer monoculture[167].Globalization,for many social greens,is little more than ecoimperialism,a process to siphon off autonomy and knowledge from the local to the global.In this way globalization is reinforcing patterns of economic, environmental,and social injustice.The globalization of production and trade, moreover,further distances an individual’s ability to perceive the ecological and social impacts of these behaviors.People are increasingly unable to see(or at least are able to forget)how their everyday choices damage the environment or injure workers.

思考题

1.What are the two broad views on the effects of globalization on environment?

2.On what points do market liberals and institutionalists agree on?

3.On what points do market liberals and institutionalists differ slightly?

4.What is the primary concern of bioenvironmentalists and what are its implications?

5.What is the main focus of social greens and what are its manifestations?

免责声明:以上内容源自网络,版权归原作者所有,如有侵犯您的原创版权请告知,我们将尽快删除相关内容。